|

|

|

|

Habitues of the D'Oyly Carte stage-door, who cheerfully waited in all weathers to catch a glimpse of their favourites at close quarters after the show, could scarcely have failed to detect a distinct pattern in their customary order of emergence from the theatre. Serious students of form could often predict the sequence to a nicety, and those in whom the sporting instinct burnt brightest were unable on occasion to resist the impulse to invest a few pence on the outcome. After the leaders had passed the post, those punters who had not sped hot-foot to the refreshment tent to squander their winnings or drown their sorrows, or were not too busy discussing the card with official stewards of the course, were rewarded for their persistence by a gratifying view of the remainder of the field.

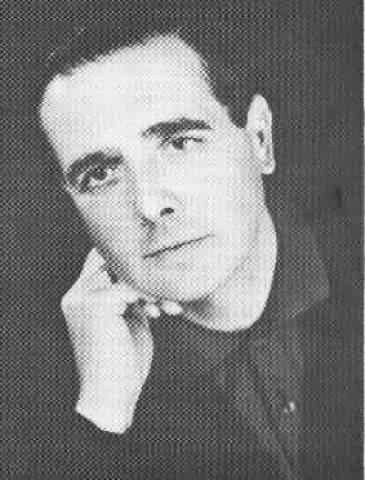

Generally among the last to enter the home straight, moving dignified and stately and his patrician features radiating goodwill to right and left, proceeded the majestic person of William Palmerley. To the many people who knew and loved Bill Palmerley and admired his work, it comes as a surprise to discover that he was not as universally familiar to D'Oyly Carte audiences as he unquestionably deserved.

Obviously nobody would begrudge the Company's principal singers their rightful share of the limelight, but Savoyards whose senses are impervious to individuality up-stage deprive themselves and do an injustice to some very professional talent. Mr. Palmerley's name received prominence in the programme only once in the non-solo character part of the Associate in "Trial by Jury" yet his contribution to performances was quite out of proportion to his modest billing.

As a member of the chorus, he was involved in every opera, with the brief exception of "Cox and Box"; his dedication and conscientiousness as an artist were second to none; and his quiet speaking voice belied a mighty, soaring tenor production known irreverently to certain of his intimates as "The Palmerley Sound". At times, especially in set-pieces like "Hail, Poetry!", a splendid vocal tone generally emanating from the rear left of the stage could be heard blending with, yet rising above, the concerted effort of the whole Company, filling the theatre and importuning the ears of the gods. Was ever singer so unsung, and with so little cause?

A native of Newcastle-upon-Tyne Bill left school to study on a scholarship at the Guildhall under Parry Jones, an excellent teacher and man of the theatre of whom he speaks with respect and affection. Not all of his fellow-students shared his opinion of Parry Jones, who was apparently of a somewhat sardonic disposition, but Bill found him a fine mentor, himself a great artist and operatic singer who had much to impart and who prepared his proteges both technically and temperamentally for the vagaries of an over-crowded profession, in which talent was in itself insufficient to ensure success. When he graduated from the Guildhall, Bill carried with him a high view of acceptable artistic standards, a personal mental yardstick with which to test his own performance, and a degree of humility which is the key to self-improvement. For a singer worth his salt, he believes that musical education begins in earnest when he first steps on the boards commercially before an audience, and the voice begins to develop with the required projection.

William Palmerley's career has been both colourful and varied. After qualifying at the Guildhall, he auditioned for the D'Oyly Carte and stayed with the Company for two years before moving on to sing in grand opera with the Carl Rosa. He has sung in pantomime, in summer shows, with an ice show which toured in South Africa, and in West End musicals like Camelot. Never afraid to diversify or try something new, he has experienced very few dull moments and has never been obliged to "rest", which alone is a commendable achievement in an occupation whose ultimate security is an annual contract and in which an artist's reputation is no better than his last performance.

In one grand opera season, he not only played a leading part in the chorus but, as its most experienced member, conducted in the wings for all the off-stage chorus work and sang at the same time! At Covent Garden, he became one of the few members of a tenor chorus ever to sing "The Trojans" in its entirety in both English and French in one year, before rejoining the D'Oyly Carte in March 1970 after a season with the Scottish National Opera Company.

His breadth of experience - particularly of his beloved grand opera - is of inestimable value, having shared the stage with some of the world's finest artists and found that a little of their magic inevitably rubs off upon the people with whom they work.

In common with the late Sir Arthur Sullivan, Bill enjoys the unfair advantage of a measure of Italian ancestry - an asset for anyone in the world of opera, and for a tenor a sine qua non. He is a tenor to his fingertips. Having a tenor voice is no mere secondary characteristic, but an integral part of his psyche, permeating his whole existence. 'Being a tenor" is a catch-phrase with which he delights his friends, whimsically justifying a plethora of idiosyncrasies from an occasionally spreading waistline to an abhorrence of early rising. His early morning manner is legendary: on one holiday, he planned a visit to Bulgaria, but got up too late and had to content himself with Turkey! (A line or two of Utopia Limited must have cost him some fleeting discomfiture.) But. if this is weakness, he never hesitates to subdue it in the cause of professional responsibility, mortifying the flesh relentlessly in order to arrive punctually at morning calls and to get into his costumes. For the average person, fluctuations in weight may usually be borne with fortitude or resignation, but for a member of the Company with a valuable and extensive range of costumes to wear in the course of duty, marked variations in weight amount to a commercial hazard and are regarded with appropriate seriousness.

Are singers a prey to hypochondria? It is possibly to be expected that people who live by their voice and appearance should be acutely sensitive in certain areas of their health. Bill needed to wind down after a show; rarely getting to bed before the small hours, and often taking time to fall asleep, his first thought on waking was an instinctive feeling for the quality of the voice. Only on Sundays and on holiday was he spared an underlying anxiety about the delicate mechanism of vocal production on which his livelihood depended, minor respiratory ailments understandably assuming menacing proportions.

Stage performers must also somehow transcend the ravages of time and maintain at least the illusion of perpetual youth. Professional singers do of course go on-stage when vocally below par, motivated in Bill's case by artistic pride and integrity, and when unavoidable must contrive to meter their output at the right moment, though Bill is personally affronted by anything less than total effort. His understanding of the essential difference between amateur and professional stagework is surprisingly not so much in terms of quality as of physical and mental stamina. The professional, though beset by sinusitis and perhaps all the cares in the world, has learned to shed his worries for an interval and, sweating under the blazing lights, to apply himself unstintingly to an ostensibly carefree performance, continuing without respite for month after month.

The glamour of the stage is but thinly spread, and without toughness, grit and dedication on the part of the performer must quickly sour. Yet improbably, for its devotees the stage remains irresistible. For Bill it is not just work, but a way of life. Despite its anxieties and ineradicable insecurity, he loves his job and prefers the most demanding operas in which he is longest on-stage. In the course of his employment, he trod the boards with equal conviction in the various guises of an entirely credible gondolier, a legitimate sailor, a blackguardly pirate, a stalwart yeoman, a Japanese grandee, an officer of dragoons, a plume-helmeted soldier, an elegant man-about-town, a periwigged baronet, a gardener, a courtroom associate, and a resplendent peer of the realm. To each he worked hard to impart an air of individual authenticity, for in Savoy Opera acting is far from being the exclusive prerogative of principal performers. Theatrically Gilbert and Sullivan is democratic in the sense that the chorus has a major part to play, its members taking a lively interest in events on-stage and reacting severally to the ramifications of the plot, while carefully avoiding any detraction from the central action; and the vocal importance of the chorus is of course enormous.

Like most singers, William Palmerley tends to judge the success of an opera by his own performance-a degree of egotism which he describes as a good fault, being closely related to artistic self-respect. Naturally enough, his favourite operas in the D'Oyly Carte repertoire are those with a consistently good tenor line, notably "The Mikado", "The Yeomen of the Guard", and "The Pirates of Penzance", though he admits to enjoying parts of all the operas.

Patience is his least favourite, having a lot of low unison singing for the tenors and patter numbers in which a profusion of consonants impedes the vocal tone; he also felt personally out of sympathy with rigid military postures and set movements with little scope for individual characterisation, and he suffered agonies from his gleaming helmet!

In leisure, Bill is a keen philatelist, devoting hours to his collection of stamps, and he shares with John Ayldon a passion for nineteenth-century French and Italian romantic opera. Of Verdi he speaks with a regard akin to veneration.

People often fail to realise that members of the D'Oyly Carte Opera Company were responsible for their own stage make-up. Glamorous make-up girls, Bill wistfully concedes, belonged to the worlds of television studios and amateur societies. Standard practice in the theatre is do-it-yourself, and, having usually received some basic training in make-up at drama school, artists quickly adapt their procedures in the light of experience and with the guidance of senior colleagues.

It may be that there are nicer guys in the world than William Palmerley, but if so they lie uncommon low. Not content with playing characters on-stage, he is a great character in his own right, a walking contradiction to those who contend that contemporary characters are no longer built on the same scale as their forebears. Bill is the antithesis of the type who oversell themselves by creating favourable first impressions whilst disappointing on closer acquaintance. Instead, not being a person of superficial attributes, he is perhaps fated to be underestimated upon casual encounter, showing how mistaken hasty judgments may be. Easy-going, rarely over-assertive, even self-effacing, Bill has a veritable wealth of personality obvious to anyone who will trouble to discern it. Although he would be far too modest ever to admit it, he is fairly bursting with qualities of warmth, loyalty, generosity, tact, sensitivity and consideration. For his friends, he will inconvenience himself endlessly. Daring to live more openly than most, he is exposed both to the best and to the worst in human nature; many of us, lacking this degree of moral courage, settle for a good deal less and make virtue of necessity.

The disappointments of life embitter some and as if in compensation enrich others, and it is to the latter category that Bill emphatically belongs. Having come to terms with his own conflicts, he is the kind of man to whom people instinctively turn in time of trouble. An attentive listener and a shrewd but compassionate observer, he instinctively finds sympathy for the characters singing almost unheeded on-stage during some of the more fascinating bits of encore business, and for the understudy hesitating in the wings before a performance who hears the audience groan at the announcement that the principal is indisposed. Given the encouragement of genuine interest, he articulates his insatiable enthusiasm for opera with eloquence and patience, and has a natural teacher's delight in propagating his knowledge and experience. He also has an impish sense of humour, unhesitatingly declaring in the presence of Herbert Newby, when someone suggested before the last night of the centenary season at Sadler's Wells that Messrs. Newby, Nash and Heyland would be well received in a burlesque of "Three Little Maids", that this tour de force was being reserved for the bi-centenary!

To give one's all professionally as a solo performer requires enormous dedication. To do so as a member of the chorus without the benefit of individual acclaim, not really knowing whether one's own efforts are approved or even noticed, con- ceivably demands even more, and only with the discipline of the highest personal performing criteria can sustained success be achieved. In a sometimes unrewarding task, William Palmerley succeeded constantly. Whether audiences always appreciated it or not, here is one tenor who never failed to do himself justice.

| Artist Index | Main Index |