|

|

|

|

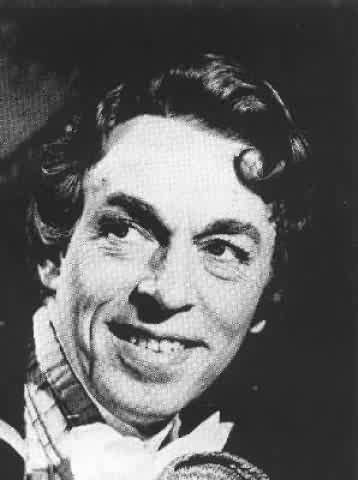

A theatrical engagement begins with an audition. So it was that on 2nd October, 1951, a certain John Reed was auditioned in Glasgow with a view to joining the D'Oyly Carte Opera Company. He had previously played many comedy parts in musical comedy with the Darlington Operatic Society - Darlington is his home town - and had been in repertory at Stockton, Redear and Saltburn. In auditioning for the D'Oyly Carte Company, on the recommendation of Eric Thornton, he was setting his sights rather higher.

Those who conducted the audition were Eleanor Evans, Director of Productions, Isidore Godfrey, Musical Director, and Jerome Stephens, Stage Manager: surely 2nd October, 1951, was a fortunate day in the annals of D'Oyly Carte when those three listened to a light baritone, voice compass G to F, of good appearance and 'pleasant quality of voice". Their verdict was endorsed a fortnight later, in Edinburgh on 17th October, when Dame Bridget D'Oyly Carte and Mr. Frederic Lloyd, at a second audition, thought him "very promising". He took up his contract on 2nd November at Newcastle-upon-Tyne as a chorister and understudy.

|

Reed's first solo part was as the Major in "Patience" a role traditionally played by the comedy lead understudy. By March 1955 he was the Judge -"and a good Judge too" - in "Trial by Jury" and Cox in "Cox and Box". He was also playing other small roles at this time, such as Antonio in "The Gondoliers". Here he showed his great skill as a dancer, for the production of "The Gondoliers" at that time required an Antonio who could dance vigorously while singing "For the merriest fellows are we".

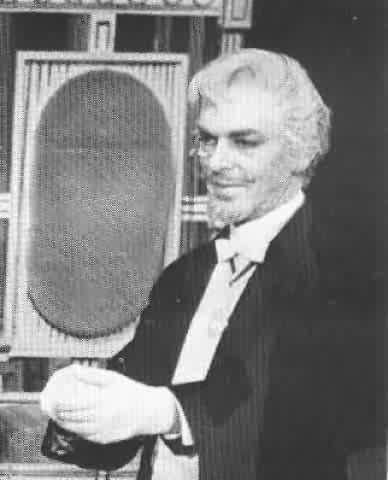

In the summer of 1959, Peter Pratt retired from his roles at the same time as illness compelled the late Ann Drummond-Grant to withdraw from the company. John Reed succeeded Pratt, supported by a new leading lady in Gillian Knight. It is never easy for an artist to wear the mantle of his predecessor (as Martyn Green found when he succeeded Sir Henry Lytton) but John Reed did not try to do so. He struck out on his own line, adapting his interpretations within the confines of the productions to his own magical stage personality. He invested his parts with wit, drive, inventiveness and subtlety.

|

When Reed took over his major roles, he dropped the Learned Judge. He resigned Major-General Stanley in 1968, but the 1970s brought him three new opportunities as John Wellington Wells in 1971, Scaphio in "Utopia Limited" in 1975 and Rudolph in "The Grand Duke" in the one-performance concert version that same centenary year (when he also resumed the Judge in the four Savoy performances of "Trial by Jury"). It was a privilege to play these three new roles, unhampered by memories of predecessors. His interpretations were entirely his own. To J W. Wells (which I think he regarded as his toughest role) he brought a cockney insouciance, a mastery of dialogue and accuracy of enunciation, breath-taking fast patter and resigned pathos as he yielded to Ahrimanes.

As Scaphio he generously subordinated his playing to Kenneth Sandford's King Paramount. Yet he could still be witty, sly, sneaky and in his dancing-as always-neat and amusing. How neatly he timed his smiles, some of them sinister, some sardonic as Scaphio!

|

His career included many highlights of D'Oyly Carte history. One thinks of the hilarity and inventive wit at the "Last Nights" of London seasons. One never knew what unexpected delight would be produced. He has sung to Prime Ministers, Lord Chancellors and First Lords of the Admiralty. He has played before the Queen and other members of the Royal Family at least eight times, including of course the Silver Jubilee Command Performance at Windsor Castle of "H.M.S. Pinafore". When the Prince of Wales, aged II, saw "The Mikado", Ko-Ko afterwards entertained him in the dressing-room.

Then, interspersed with touring in England, Wales, Scotland and Ireland, there were eleven overseas tours, exhausting occasions which demand much travelling and acceptance of social invitations when an artist would like to relax informally. Reed was a chorister in the 1955-56 tour to the United States and Canada, but it was as principal comedian that he ten times led the company overseas since 1962, culminating with the visit to Australia and New Zealand in 1979. The responsibility and physical exertions of these tours, with much air travel, are seldom appreciated, and to a sensitive artist the strain is considerable, yet it is John Reed's reward that he won many international admirers. It was altogether fitting that he was appointed an Officer of the Order of the British Empire in 1977.

|

Memory will want to recall just a few of his particular touches. One thinks of Sir Joseph Porter, proud, stiff and smug, who speaks with condescension and during the encores to the Act II trio signals in semaphore for help and jumps overboard (both these pieces of business he invented himself; he did not inherit them).

As the Major-General, he would sing his song effortlessly on the top of his voice at breath-taking speed. "A washing-bill in Babylonic cuneiform" is an absurdity: Reed makes the preposterous idea sound amusing. Reginald Bunthorne, quietly persuasive, is sly in his singing of "If you're anxious" and selfish when he removes the engagement ring from Patience as Grosvenor arrives, in the Act I finale.

His Lord Chancellor had an inner humour and cheerful grin when bestowing pretty girls; it is a lawyer who speaks about affidavits and the rules of evidence; it is a friend who sings about excessive professional licence. There is a smile as he makes that exit. In the dance to the trio, he always delighted when he stops his unprofessional dance just before Lord Mountararat can reprove him. All in all, a study in which Reed can take "legitimate pride".

|

King Gama is an interpretation which I always enjoyed. How magnificently did Reed dominate stage and audience in that fine opening song and the ensuing dialogue. Here Reed recalls a now past school of acting, when with crusty venom in his voice he baits Cyril and teases Hilarion. Dry, royal and waspish, note how he phrases the line "erring fellow creatures". Note too how Reed speaks with pride of the eight virtues of his daughter, leading up to the great climax of "I am no snob".

Ko-Ko changed over the years. Once rather vapid, perhaps even light-weight, with elfin-like dancing, it matured into the cheap tailor out of his social depth. He had the lightest of touches in "irritating laughs". There were nearly always topical and amusing substitutions for "the lady novelist" and "Knightsbridge" (for example, "Sadler's Wells", when that organisation started its own presentations, and "referendumist" at the time of the Common Market vote). He dreamed up some new business for the encores to "Here's a how-de-do". Having delivered to Katisha his "white-hot passion" at breathless speed, he speaks the ensuing lines "I will not live without it" and "I perish on the spot" as no other Ko-Ko in my experience - he appreciates their witty double-entendre - and then, having convulsed the audience with laughter, he sang "Tit Willow" with extreme tenderness and sincerity.

|

Sir Ruthven Murgatroyd is no easy part - indeed, it is really two roles. Shy and conceited in Act I, good and modest in Act II, there was always a cheeky "Yes, uncle" at the end!

Jack Point will, I think, always be my favourite John Reed part, although "The Yeomen of The Guard" is not my favourite opera: the "Hamlet" of Gilbert and Sullivan roles, said Reed in a chat-show interview.

It is not always realised Jack Point has only five scenes in the opera, two of them very brief. Reed took these skilfully to show the change in Point's fortunes. His Point is not engaged to Elsie, but he regrets this omission, as soon as she marries the unknown prisoner. He knows his jokes to the Lieutenant are not too funny. Melancholy when reading Hugh Ambrose, ironic as he sings to Wilfred Shadbolt with all his customary clarity of diction and irony, unashamed in the "shot" scene (for which he adopted a paler make-up), you could see his suffering in Fairfax's wooing of Elsie and in his exquisitely tender "When a jester Is outwitted". And those final moments, as he pathetically tries to recapture the affections of Elsie's affections which he never really held - and then with a half-laugh he has a fatal heart attack. A small point, but when Reed fell, he knew how to rull over half the stage and send a shiver up the spines of his audience.

|

In "The Gondoliers", by contrast, the Duke of Plaza-Toro is vocally immediately martial, elegant, stylish, and abounding in Gilbertian inner-humour. A courtier grave and serious, indeed, whose dancing skill reminded one yet again that Reed is a dancer on the stage of very great ability. Burlesque ballet steps exaggerated, yes, but not to inartistic limits.

Fortunately, he has recorded for Decca all his roles, some more than once. Memories can be refreshed by playing records at home. when one can recall his nuances of expression. It is for this reason that this appreciation has concentrated less on his considerable musicianship and more on his personality as an actor. The two, nevertheless, go together. If unexpected joie de vivre breaks out at a London "Last Night" (as when in 1979 his Bunthorne had 'Barclays" tattooed on his chest), he has never forgotten that Gilbert and Sullivan are humorists of word and note, and he has been a great interpreter of both. For nearly three decades of giving pleasure, one can say quite simply: thank you, John.

| Artist Index | Main Index |