|

|

|

|

When superannuated spinsters casually refer to their boyfriends in the course of conversation, one tends to raise the eyebrows - one exhibits surprise. Even when one knows perfectly well that age is deliberately amplified by a skilful contrivance of padding, grease-paint and grey-haired wigs in anticipation of another episode in the life of Rederring, the stigma of advanced years still stubbornly clings. Neither is the impression much allayed by an unremitting public confession of rampant physical decay. In Miss Holland's case this is all incontestably unjust. On-stage she may indeed require the full assistance of strategic lighting in order to pass for forty-three or anything like it, but reality reveals her as youthful, blonde and even something of a whizz-kid. How else to categorise someone who achieves D'Oyly Carte principal status after only two years' professional experience?

Lyndsie would have you believe that her whole career simply happened, more by chance than design. She was born the youngest of a family of eight children in Stourbridge, Worcestershire, with more than ten years separating her from the next youngest child and evidently, by her own admission, a mistake! She grew up with nephews and nieces rather than with her much older brothers and sisters, went to the local primary school, and somewhat to her surprise gained a place at Stourbridge High School, where she sang in the school choir but without distinction. After leaving school she did clerical work for a time and later became telephonist to a Birmingham firm of stockbrokers. One day a friend who wished to enrol for piano lessons took her along for moral support, and out of curiosity Lyndsie made enquiries about singing lessons. She took a few lessons (as a soprano) and a little theory, felt she was getting nowhere, and eventually gave up. She took part in a couple of musicals staged by amateur societies, lost interest, and was eventually persuaded to audition for the Midland Music Makers, a Birmingham-based amateur operatic society. Before she had even served an apprenticeship in the chorus, she was offered the mezzo-soprano lead in "Prince Igor", hesitantly accepted, was heard by a talent scout from Sadler's Wells Opera, who she presumed was in the auditorium to listen to someone else, and on 23 September 1968 found herself in the Sadler's Wells chorus. Two years later she heard of a D'Oyly Carte vacancy, auditioned at the Savoy, and joined the Company in December 1970.

|

It all sounds too easy to be true, and of course it is. The rest of the story begins with a little girl of ten, obsessed even then with an ambition to go on the stage, who with laudable foresight had devised her future stage name from the maiden names of her grandmothers. She always enjoyed singing, shared her brother Arthur's taste for operatic music, and from his record collection gained a repertoire of tenor arias of which many tenors would be proud. Through the Midland Music Makers she discovered to her disappointment, at the age of twenty, that she was a contralto, and set herself to enhance her technique, overcome nervousness, and improve her self-assurance. After first auditioning for Sadler's Wells, she turned down the offer of an engagement until she had further pursued her studies and acquired additional experience, already cultivating exacting, self-imposed artistic standards and displaying that rugged discipline and dedication which seems to be the hallmark of the successful professional singer. Her first D'Oyly Carte performance was in the role of Lady Sangazure - the first D'Oyly Carte contralto to play the part since 1939.

Upon first joining the Company, Lyndsie had to absorb simultaneously no less than ten principal roles - a feat which will be appreciated by anyone who has struggled to master just one part for an amateur production. She observes calmly that the facility for assimilation develops with practice, mentions that at Sadler's Wells she played in twenty-three operas, and cites the case of a typical repertory company who at a given time are likely to be performing their current piece, rehearsing the next, and learning lines for the one after that. She counts herself fortunate to have a quick grasp of new situations and a retentive memory, which perhaps is just as well, as she had more parts that any other D'Oyly Carte principal singer. When the full repertoire was being played, colleagues have a free evening whenever an opera in which they do not appear is being staged; having a major role in every full-length opera, Lyndsie had to depend for an occasional night off upon the able covering of Beti Lloyd-Jones.

Lyndsie's professional talents, like Private Willis, were generally admired. By any standards her vocalisation and range are outstanding, and it is no secret that Sadler's Wells were particularly sorry to lose her services. Many people of informed judgement regarded her voice as a quite exceptional instrument which may arguably not find supreme fulfillment in the works of Gilbert and Sullivan. However, Lyndsie herself is the first to take issue with singers who minimise the difficulties of performing Savoy opera; in many respects she found it more exacting than grand opera, not least because, in the absence of sung recitatives, the singer has the task of setting the scene from the very opening notes of an aria.

|

No-one could accuse Miss Holland of having allowed success to go to her head. Honest, forthright, likeable and unassuming, she has a well-formed sense of humour and a superbly hearty laugh which would not disgrace a hunting-field. People in the Company found her sociable, generous, tolerant and considerate, with a frequently infectious inability to control her amusement on-stage.

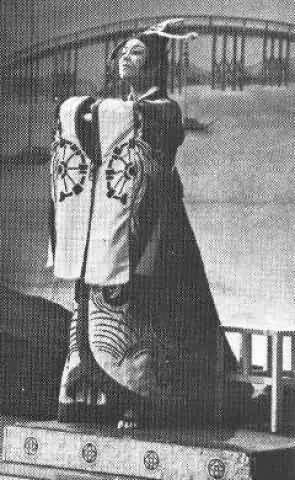

Lyndsie derived a good deal of satisfaction from representing her 'old bags', as she affectionately styles the formidable bevy of womanhood whom she animated on-stage. All are sufficiently alien to her own personality to create a constant challenge, and she tried to stay in character the whole time, reacting credibly to all the events of the plot. A rapport quickly developed with colleagues whose work is equally wholehearted, and she aimed to impart genuine individuality to all her roles. Often she began with a particular person or type in mind as a model, and found that full complexity of characterisation grew with experience. There is infinite scope for experiment, shades of meaning varying with the slightest shift of emphasis, and staleness and boredom can never co-exist with a good audience. She enjoyed playing the Duchess of Plaza-Toro, found Dame Hannah the most sympathetic, and Katisha the most satisfying part both musically and dramatically. For Lady Jane she had a special affection, as well as for the rather distinctive Patience' audiences, despite for her the daunting solitary exposure of the beginning of Act II, and she welcomed the opportunity in 1975 to appear in "Utopia Limited' and 'The Grand Duke'. Gilbert, she feels, was not very charitably disposed to female characters in general and to hers in particular. She is not incidentally among the number of those who lamented the omission of 'Come, mighty Must!' in "Princess Ida".

The authentic splendour of D'Oyly Carte costumes elicited Lyndsie's praise, but her admiration was tempered by a strong personal aversion to crinolines, of which she had to wear a substantial number. Learning to drift elegantly around in them is something of an art, and the fashion unhappily did rather less than justice to her figure. Lady Sangazure's crinoline was patently the worst and was unquestionably designed to accommodate a quadruped. Problems also arose with Ruth's pirate hat, the felt brim of which absorbed sound so efficiently that the singer could not clearly hear her own voice, and with the armour worn for the final act of "Princess Ida", when Lady Blanche must choose between keeping her arms by her side and instant asphyxiation.

|

Lyndsie has an entertaining fund of funny stories about life in the Company which she generally relates with unashamed glee. Fans may have been occasionally privileged to see the gondola fail to reach dry land in the first act of "The Gondoliers", but they would rarely have been aware of the appalling consistency sometimes achieved by the spaghetti or the unspeakable foreign bodies which occasionally manifested themselves therein. She treasures memories of some remarkable ad-libs nurtured by necessity, including a whole verse of spontaneous 'Japanese' for which she herself was once responsible. There was also a frequently savoured moment when she managed to drop John Reed in "Patience" whilst in the act of bearing him bodily from the stage - and which to this day she swears was an accident. On another occasion following a bit of off-stage banter before a performance of "Ruddigore", Kenneth Sandford delighted his hearers by inadvertently claiming young Strephon as his elder brother!

Lyndsie has a high view of her chosen profession and of the art of singing, accompanied by a connoisseur's admiration of supreme talent. Having a profound respect for the voice, she objects to vocal clowning but equally feels that the instrument should not be pampered. Her experience in the chorus has led her to the conclusion that choristers can sing within their own limits with reasonable but not excessive vigour and give good performances without vocal damage or strain. However, instances elsewhere in the operatic world have come to her notice where young singers have been offered demanding principal roles too early in their careers. which is naturally gratifying if they do not recognise the risks thus run by immature voices. Lyndsie has known artists 'sung out' by the age of twenty-five - a form of exploitation which she finds hard to forgive. She additionally regrets that some singing teachers give encouragement towards a professional career in certain cases where such encouragement is not in fact warranted, in the long term it may be kinder to face the reality that their pupils are acceptable singers but do not have the physical or mental stamina to succeed in a stage career.

Without doubt Lyndsie herself has an eminently sensible, both-feet-on-the-ground approach to her work, without which the greatest talent seems unable to survive in a tough, arduous and sometimes fiercely competitive profession

| Artist Index | Main Index |