|

|

|

|

It has been said somewhat jocularly that you specialise in ecclesiastical roles-for instance, the Don and Dr. Daly, which seem to be two of your better parts.

Oh no - I don't specialise in them. I think it's the result of a few quips that I have made - but I do enjoy them. Perhaps the fact that I've sung in a local church choir for many years helps. I have a lifetime's experience in observing members of the clergy from close quarters-not that I based Dr. Daly on anybody particularly.

It seems to have worked out as one of your best ever roles with the Company, Dr. Daly. You seem to enjoy doing it, and wherever you go you get the most fantastic press for it, often stealing the notices.

Thank you ... well, I think perhaps it's because "The Sorcerer" is a new production and I've had the opportunity to use the experience I've gained over the years playing G. & S. to create a new role. All the other characters I play are in productions as played when I joined in 1957, with the exception of the Grand Inquisitor. Mrs. Darrell Fancourt was in charge of presentation then, and she was a member of the "old school". She taught me all my roles and tried to make me understand that there was a definite style to playing the G. & S. operas. Naturally enough - and in spite of the fact that I had had quite a number of years' experience playing juveniles and various odd characters in musicals, revue, and a little opera, I took this to heart. She was quite a formidable producer and quite insistent that Gilbert and Sullivan needed a different approach from anything I had done before. Wishing to learn the mysteries I made myself very receptive to her ideas. I think I took in much more than I should have done, because through the years I have found that there really isn't such a thing as a traditional way of playing Gilbert and Sullivan. There may be a D'Oyly Carte way of playing Gilbert and Sullivan. The important thing is that both the libretto and the music should be treated with the greatest respect. That doesn't mean to say that they should not be done without a twinkle in the eye.

Which were your first roles in the repertoire?

I did them all. I learnt about eight in eight weeks, and before I knew it I was on the stage at, I think it was, the King's at Southsea, and I was in full repertory with "The Mikado" Monday night, "Gondoliers" Tuesday, "Iolanthe" Wednesday, "Ruddigore" Thursday, and "Patience" Friday. It takes a long time to settle down, of course, because if you're playing "Patience" once a fortnight you only do twenty performances a year, or twenty-five at the most, and you're so concerned with the other operas in between that once you've finished one opera you're into another. You haven't really had time to start pulling the thing apart; you can't start thinking along the lines of my earlier training. In a production in the West End with American producers you're produced tightly. You move around the stage at each performance to within a foot of where you're supposed to be. Very tight. (In fact, the difference between the musical comedy productions and these was not in that respect; so how on earth can the critics always get at us by saying how can we repeat these things time and time again, when in actual fact this applies to every long-running show?) You get people who have been in productions for two years; well, they've done exactly the same thing that we do, but at least we have the change every night. I've been brought up along these lines. I took the production as I'd always been taught, but then I'd also taken on this fashion of almost being a puppet. It's difficult to see characters in these G. and S. operas because their plots are sometimes very complicated and the lines contradict some thoughts you may have. You work along nicely in the first Act, and then suddenly in the second Act you find something contrary to the way you've been thinking.

|

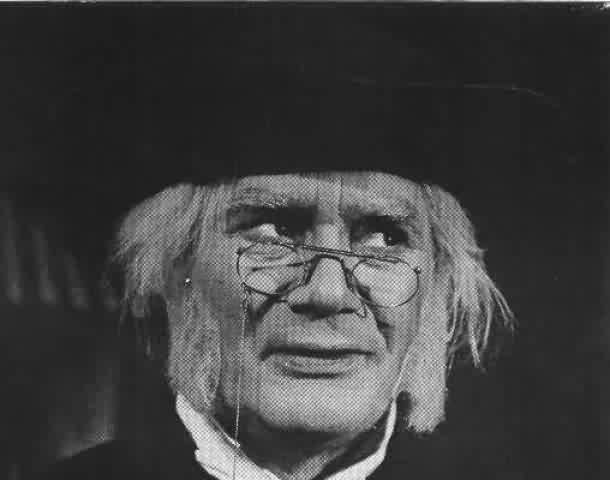

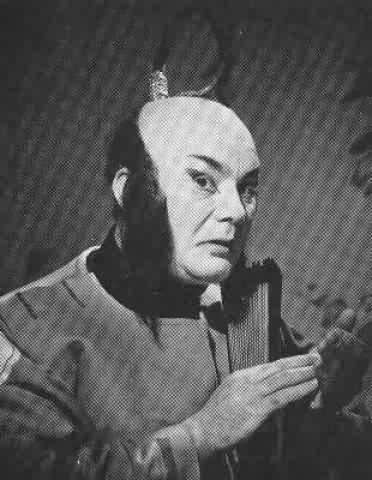

Anyway, I've found that, after going along blindly for a couple of years, I started thinking a little bit. I can give you an instance: a character like the Grand Inquisitor. The emphasis was not on the fact that he was a man but that he was a Grand man. He was a Grand Inquisitor, which was the interpretation put on it, and I think that most of my predecessors thought that too. He sort of lorded it over the stage, and was one of the aristocracy; he looked at everyone down his nose, and nobody could touch him.

But now, you see, I've been given a new dimension. I was allowed to make him a person - you know, somebody who is susceptible to pretty girls. And all the lines in the show point to this. Whereas there was never any encouragement to put emphasis on these lines in the past, now I'm allowed to. Consequently I'm a Grand Inquisitor by name - and let's face it, that's what people are, they're just given handles, it doesn't change them as people - but I'm also a man. So I can work on a character within that and still appear in my robes and everything else. This means I can have much more fun, and I'm not hidebound to the conductor in the pit. I'm aware of what the conductor does, but I don't have to look between his eyes to see what his beat is. I can look up into the gallery and still be aware of what he's doing.

A lot of principals come almost straight from music college and work their way up from being choristers in the company, whereas you came from being a principal in musical comedy in the West End and a very seasoned performer, although you were still a young man when you joined D'Oyly Carte.

Well, it's a tremendous advantage, there's no doubt about it, because it's only through experience that you realise what a wealth of expression you actually have at your command on the stage. It took me about two years to get rid of the shackles of my first producer, and then I started using my imagination, which had been subdued until then because I had been told that there was a particular style. But it takes a long time before you can realise in how many ways you can say a particular line and also as a different character. And so one starts pulling it around and making it one's own. You still don't have to change your position on the stage, of course. That is one of the exciting things about working on the stage. You take all the limitations that the producer gives you - he says, "Right, you've got to walk over here four paces (or whatever it is), you've got to be in that position there, you've got to turn round on this word because the light is over there, you've got to be in a position to be able to get to stage position so-and-so"; you take all these, but then the challenge is to DO A PERFORMANCE. Accepting the limitations and making it appear there aren't any is a marvellous thing. This is one of the challenges that I like and why I've enjoyed doing the new productions.

It's always annoying when you hear a young performer who has come from a college or something like that saying to the producer "I don't feel it this way." You know, young performers are employed to feel it the way the producer wants them to feel it, and they should take on the limitations, and then do a performance, in spite of the limitations, as a challenge.

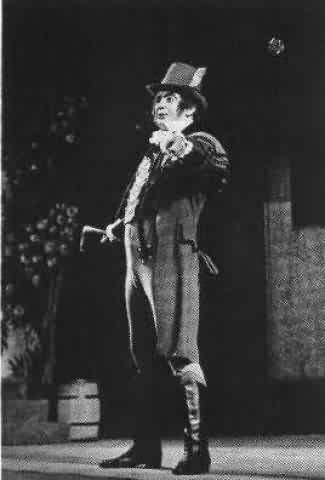

This is what I've found. Of all the roles I suppose "The Gondoliers" and the new Sorcerer roles play particularly well for me, mainly because I've been able to rethink them completely. The others have changed tremendously since I first started, but we haven't had the advantage of new productions, which of course limits one to start with.

My Despard now bears no resemblance to the "Ruddigore" role I did when I first joined.

Well, obviously you have worked on it.

Yes, it's bigger, broader, and I'm no longer hidebound by the tradition of always facing out front, which was the case. You know, if two people were on stage it was very seldom that one was allowed to face the other person to say one's lines; one was always directed to face out front. Fortunately I don't have the handicap of having a soft voice; but you still don't have to turn out front to get dialogue across if you want to. But these limitations were very much imposed to start with. There may still be a lot of people who do not agree.

|

We're not discussing who is agreeing with you; we want to know exactly what you feel. Your "Ruddigore", for instance-are you still working on it?

Yes, the "Ruddigore" I did on Thursday night was quite different from the "Ruddigore" I did nine months ago. We haven't done it for that length of time. But I suppose the thinking that I've done on a lot of roles has gone on subconsciously at the back of my mind; and I found that quite extraordinary inflections came out on Thursday night. I mean, the same words and the same music and a lot of people may say they didn't notice any difference, but the thing is that such changes help to keep the operas alive - or one hopes that they do. People say "What fun you have doing them!" Well, you couldn't possibly give the impression that you're having fun or that they're fresh unless you are continuously thinking - actually when you're working - about what you're saying and doing.

This is the exciting thing I find with John Reed. I work with John or with Peggy Ann Jones - they are the people I work with most often on the stage - and I find them just as exciting, because all the time they're seeking new stuff. We start a slightly different inflection; maybe people Out front - they've been there the previous night - wouldn't notice anything different. But we do. And it gives us the reason then to put the emphasis, maybe slightly, in a different place. Sometimes it doesn't work, of course. This is the inevitable thing about experiment. One night it will work marvelously, and another time that slight inflection won't be right. But then again a lot of the audience would not have noticed, anyway.

But then the great traditionalists amongst the audience would, wouldn't they?

I'm not so sure. There are certain things you've got to do at each performance because you cannot do them any other way. For instance, if you've got to flick a fan while you're in the middle of a musical number obviously there is a time when you can do it and when you can't. So it's inevitable that it will come in the same place; and if it's traditional to flick your fan there, fair enough, then it's tradition.

And there are punch lines, of course, to which you can maybe give a little more innuendo, and they may have a more modern meaning than they ever had before. So one can, without dwelling on it too much, always put that little bit more emphasis on it to make it a little bit more topical. I suppose a case in point is the stuff about Fairy in "lolanthe" at the end when they say "How would you like to be a Fairy (Guardsman)?" You see, in the past I'm darned sure that nobody ever did a double take when she said that, but I'm equally sure it's the legitimate thing to do now. The audience think it is. You don't make it nasty or anything like that - you just use the modern sense of humour.

Can you think of any other lines which have more impact today than they used to have?

Well, we had a very good one last night: "This comes of women interfering in politics", which of course was on the day Miss Devlin assaulted the Home Secretary, and which brought a roar of laughter. There's always something appropriate, funnily enough, which comes along.

To go direct to the heart of the matter, Ken, which part in the repertoire would you say was your favourite?

|

I don't really have a favourite; I enjoy playing most of them. Particularly - and one always says this assuming that one is feeling on top of the world, fit and fresh, and the voice is not full of frogs, or one has not got a cold or anything like that - I enjoy "The Gondoliers" very much and I enjoy "The Sorcerer" very much; one of my favourite roles is Grosvenor in "Patience", which I find highly amusing but very exacting. I like Shadbolt very much; this is great fun, although, strangely enough, it's one of the shows I dislike playing in a matinee. I find that in a day, if I do two performances of it, it's not that I get tired of it - physically tired, I mean - I get mentally tired for some unknown reason. The only thing I can put it down to is that I wear a most miserably-coloured costume and that I'm dirty, so that I feel unshaven, and it seems to have some sort of psychological effect on me. But I always feel a bit down after two shows.

You talked earlier of your work on "Ruddigore".

"Ruddigore" I enjoy tremendously; that's a real good laugh now. But I must say that if I had to do it for a week I would be rather worn out, I think. I find I have to give so much in the first Act that the second is quite an anticlimax physically, although of course Peggy and I have a lot of fun playing that, particularly with the new approach we had on Thursday night. One is continually looking for new meanings. You see, it's so easy to do. In the old days I used to say: "We have been married a week" in a stentorian voice that had to go to the back. And now, of course, I can make it quite different - gentle.

I think perhaps we tend to under-estimate the number of people who might appreciate these subtleties. Well, you see you can play with words the whole time; even with the bang off-stage that we now have in the second Act - "But soft, someone comes." We put that in, oh this is quite new, and I've even changed "But soft, someone comes." in the old days it used to be (loudly) "But soft, someone comes." Now it's "But soft, someone comes" underplayed tremendously. So it's different. All the time it's moving. It has to move; if it didn't I wouldn't be here. Because I'm quite sure you'd go scatty playing the same parts if you didn't get a lot of fun out of them yourself. You may get tired of the idea of doing them; John does more shows than I do, but I do an average of seven shows a week. I've done virtually a performance each day of my theatrical life, and fifteen years of that have been with the Company, so each evening when you get on the stage you have to come to it as though you had never said the lines before. Mind you, sometimes it comes over that way! But you have to give the impression that you're thinking of the lines for the first time, and this is a tremendous challenge. I can't imagine going on the stage and not thinking that. it's a sort of way of life I've got used to now. John's the same - we often talk about it - and he says too, "If I didn't go on there and sort of be aware of all the little things that can change your inflections - anybody that's slightly out of position or something like that, it means there's a change in inflection." It's got to be. If I wasn't aware of things like that then, as he says, he wouldn't do it -couldn't do it. This is the exciting thing. You go on there, excited - people might pooh-pooh the idea that you can get excited about Gilbert and Sullivan; I mean, I never got excited about G. & S. before I joined the Company. I get excited about playing it; I get excited about it when I'm talking about it; but that doesn't mean to say it's a be-all and end-all as far as I'm concerned in a theatre. One is a professional, and I'm sure this applies to John and every other member of the team.

|

You've done fifteen years with the Company at an average of seven performances a week. Do you in fact keep a tally of your individual roles played?

No, I don't. But if you say fourteen years of playing "The Mikado" once a week - it works out more than that. It's three times a fortnight - I suppose one could say that one could do "The Mikado" for a hundred performances a year. I should think I must be on the 1500 mark for "The Mikado" and for "The Gondoliers".

The Gondoliers to me... I can still hear Besch suggesting that I did that this way and that way; and I do it if I'm in that sort of mood.

That was one of the great turning-points for you?

Yes, I think it was, and of course I was very fortunate in doing "The Yeomen of the Guard" at the Tower with Besch for the Festival of the City of London. That gave me an insight into Wilfred, too, because it was a different approach. And of course it was at the Tower itself. That must have had a big influence on my interpretation here. That was a milestone, and I'm hoping that they will slowly work through the whole repertoire like that, because it gives so much of a stimulus to the whole Company; and we need it when we do the operas so often. It's marvellous to he able to come into rehearsal when somebody there is alive with the possibilities of this opera. I mean, I could drop my interpretation of any role that I play tonight or tomorrow night if someone came along and said "I'd like to do a completely new production of this, that, and the other, and I want you to re-think your part. Instead of playing Pooh-Bah as a fat man, play him as a thin man with a lisp or an accent." I would find this a tremendous challenge. I'd love to do it, because I don't go along with the idea that the operas can only be played one way. But on the other hand they've got to be done the right way.

| Artist Index | Main Index |