|

|

|

|

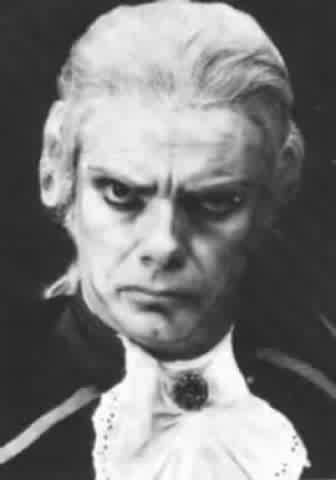

Fans meeting John Ayldon off stage for the first time were usually surprised to discover that he was neither as old nor as tall as they had anticipated. With the Pirate king, Colonel Calverley, Sergeant Meryll, Dick Deadeye, Sir Roderic Murgatroyd, Sir Marmaduke Pointdextre, Arac and the Mikado of Japan looming large in the memory, the misconception is understandable enough, for only in "Iolanthe" did John appear in anything approaching natural guise. The stage illusion is at once a tribute to his skills in make-up and characterisation, and a reflection of the nature of the roles he played. Unlike Mr. Ayldon himself, his characters in the main have passed - and even forgotten - the flower of youth, and in the main also they are villains.

True, the quality and degree of their villainy differs, but each boasts at least a spark of mischief which John portrayed with conviction, even with relish. Clearly his own sense of fun, if not of villainy, found an outlet through his work, and the audience may not have always been fully aware of it. It was frequently instructive to observe his behaviour while the action was temporarily centred elsewhere: at one point in "H.M.S. Pinafore", for example, the faces of the chorus grouped in a semi-circle presented an interesting study as he passed before them with his back to the orchestra! In John's view, humour on-stage is more nearly a necessity than an optional extra. He is at pains to point out that he uses humour sparingly, always in character, and never at the expense of the action; but, given these stipulations, it helps to relieve the tensions and fatigue which inevitably accumulate during a long tour, normal D'Oyly Carte practice being to work for an unbroken spell of forty-eight weeks before taking a holiday - a prospect which amateur performers might view with pardonable apprehension. Performing exclusively in the works of the same composer and librettist is not without problems for the creative artist, giving rise to a continual need to ring the changes mentally, and a sense of humour is invaluable in helping to retain a quality of spontaneity.

John Ayldon also has the happy flair of being able to ad-lib. when things go wrong, which can happen occasionally even with a professional company playing familiar roles. Contrary to the pretensions of "Iolanthe", artists are fallible mortals after all, who may be tired or worried or unwell, or may simply suffer a mental block, which in the patter songs in particular is all too easy. Problems can also arise from extraneous factors quite beyond the control of the people concerned. Sometimes the audience senses that all is not as it should be - generally much to its delight - sometimes it does not, either because the flaw is a minor one or because it happens off-stage. During a performance of "The Yeomen Of the Guard" at Norwich, Kenneth Sandford burst from the stage at the close of a dramatic scene and came to an abrupt but temporary halt against a door in the wings, which promptly flew open to deposit him unceremoniously face down in the good East Anglian earth outside. From the stage, John Ayldon and Lyndsie Holland had a view of this affecting spectacle which, had it been available to the audience, would have justified a minimum surcharge of 10% on the price of all seats in the house, and, supposedly by reason of natural concern for their colleague, were rendered incapable of further dialogue. In such circumstances, the ability to improvise is a pronounced advantage, so that difficulties are minimised or even appear intended, and John counts himself fortunate to have it.

Unlike many members of the Company, John Ayldon joined the D'Oyly Carte from the amateur stage rather than after graduating from formal studies in music and drama - an achievement which enheartened many who presented themselves for audition. Born in London, he went to San Francisco with his sister in 1954 where he made his stage debut at the age of twelve, playing a juvenile part for a three-month season and appearing on television shortly afterwards as Huckleberry Finn.

|

Returning to England in 1958, he first encountered Gilbert and Sullivan from the ranks of the constabulary in an amateur performance of "The Pirates Penzance", but, though he had always been keenly interested in the theatre, it was some years later before he first seriously contemplated a stage career. In the meantime, amateur companies provided him with a good general knowledge of the Gilbert and Sullivan operas, and he also gained valuable acting experience from many amateur performances in South London as well as from a spell of semi-professional repertory work in the north of the city; but his bread and butter continued to be earned in the worlds of journalism, shipping and advertising, until in 1967 he was invited to audition for the D'Oyly Carte Opera Company

Not only was he promptly accepted for his first fully professional theatrical engagement as a member of the Company's chorus, but only two years later he was promoted to the exacting range of principal bass-baritone roles vacated by Donald Adams, whose help and advice were always freely available and with whom John remained on terms of friendship until Donald's death.

With characteristic modesty, he attributed his swift rise to prominence to his good fortune in being in the right place at the right time. Certainly there is truth in this, but equally certainly it is less than the whole truth, for it pays but scant regard to the conspicuous vocal and dramatic abilities which won him such widespread admiration. Genial and good-natured, with a natural exuberance and self-assurance, John Ayldon is a person who excels in company and enjoys popularity both socially and in his work, where his distinctive contribution to the life of the Company was respected and appreciated. His approach to life is brisk and positive, as anyone who has tried to walk down a street beside him will have discovered, and he possesses a robust constitution, missing few performances through illness, much to the disgust of his understudies. There is about him an inescapable strength of character, and an honesty and courage which do not shrink from an awkward situation, but his resolution is tempered by an essential courtesy and generosity of spirit which frequently lead him to the defence of others. One senses that hidden depths lie beneath the extrovert exterior, and that fundamentally John is a very private person; if this is an instinctive defence mechanism against the publicity of the life he leads, few would begrudge him its consolation.

John is one of the fortunate people whose work is also his hobby, though outside working hours his taste ranges over the whole field of opera and beyond. Italian and French romantics of the nineteenth century are a source of great pleasure for him, Verdi and Donizetti being especially favoured. As a touring performer, he had little opportunity of seeing stage performances of other works except perhaps occasionally in dress rehearsal, and so had to rely mainly upon records and broadcasts, to which he listened with the same discriminating critical faculty which he applied remorselessly to his own work.

According to John, the glamour of the stage is perceived principally from the auditorium. The reality consists at times of unremitting toil in rehearsal and performance, unsocial hours of work, endless travelling, and the physical and nervous strain imposed by long tours with up to eight performances weekly. Anyone who fancifully imagines that the Company enjoyed a 2 1/2 hour working day needs to bear in mind that an audience sees only the finished product; if a dramatic illusion is to be successfully created, the problems of production must not be apparent. In another sense, the product is never finished: it is a dynamic concept demanding the maintenance of high standards of performance, before audiences intimately acquainted with the operas, by a continually changing company of artists, all of whom are subject to the variations of health and temper common to humanity. To achieve something approaching uniformity of execution, even with a limited repertoire, is the result of constant endeavour. A further bit of anti-glamour for most people is the rootless, nomadic existence which perpetual touring involves; John kept a London flat which he could occupy only during the London season and at weekends when he was working within reasonable travelling distance of home. On tour, he usually shared accommodation with friends in the Company, preferably renting a house or flat where he could install his mobile kitchen, indulge his talent for cooking, and come and go and take meals at the odd times necessitated by his work. Yet, paradoxically, in spite of sweat, tears, and living out of suitcases, for one into whose blood the theatre has entered there can be no other life.

If an element of villainy is the common factor linking the numerous characters whom John portrayed in the operas, he refused to feel himself type-cast. All the parts are quite different, and, although the singing voice obviously remains fundamentally the same, he did his best to bring a distinctive approach to each one.

. |

When asked the inevitable question as to which is his favourite production, he hesitated between "The Gondoliers" (his night off!) and, more seriously, the role of Sir Roderic Murgatroyd with the beautiful vocal line of "The Ghosts' High-Noon", and the busier stage part of Lord Mountararat which embodies the stirring bass aria "When Britain Really Ruled the Waves". He enjoyed the characterisation of Sergeant Meryll, the Pirate King, and Dick Deadeye; in these roles and in that of the Mikado, his stage movements were not too strictly circumscribed and he found that he had some degree of artistic freedom. About Colonel Calverley he was less enthusiastic, enjoying the performance only after his difficult opening number had been successfully negotiated (and who can blame him?), but he reserved his chief displeasure for Sir Marmaduke Pointdextre, who seemingly spends much of his time as a species of gentlemanly master-of-ceremonies making announcements to the assembled company usually from the back of the stage and occasionally through a pall of smoke.

This exemplifies one of the inherent conflicts in the production of the operas - the conflict between the needs of the performer and the dramatic requirements of the piece in terms of costume and effects. ideally, a singer prefers to work with head and neck unrestricted, and welcomes recording sessions and concert performances in consequence, but on-stage he is variously subjected to beards, wigs, helmets, suits of armour, sound-absorbing felt hats with broad brims, and high-fitting tunics, all of which conspire to impair the vocal effort from the singer's point of view. In "The Pirates of Penzance", for instance, John wore a tall felt hat, luxuriant moustaches, full length periwig, voluminous padding around the waist and chest, an enormously heavy coat, and boots with built-up heels in which he tottered around on tiptoe and which developed his calf muscles to an extent seldom encountered outside the bounds of professional sport. Only in the second act of "Iolanthe" did John appear relatively unencumbered, but he accepted these restrictions philosophically; they are an inescapable part of the job, and the challenge is to overcome them, get into the right frame of mind, step on to the boards and give a performance.

Another conflict for performers is the periodic clash of the demands of words and music, which on more than one occasion provoked a frank exchange of views between Gilbert and Sullivan, and persists to this day. In Savoy opera the words are of singular importance, John feels, and simply have to be enunciated, sometimes regrettably at the expense of the music. Professional singers in other fields generally seem to agree that the works are not easy to perform well, the patter songs especially proving a fruitful source of difficulty.

In answer to a further predictable question, John Ayldon has to admit that constant repetition of familiar roles does carry for the performer a serious risk of staleness - a hazard encountered in any long-running theatrical production. Awareness of the danger helped him to guard against it, but to succeed completely all the time is virtually impossible. Some roles he found more prone to staleness than others. One of the best safeguards against it was the customary touring practice of performing a different opera each night, compared with the normal London season procedure of playing just one or two operas per week, which from the artist's point of view is appreciably less attractive. In a week of staging "The Mikado", for example, a singer might sense that his performance was just beginning to lose its edge by midweek, although he could well be back to peak performance by the weekend. These nuances are hopefully not communicated to the audience, but the singer has to work harder to maintain his original level of commitment. Two factors which assist him are his own sense of creativity, and audience participation: only an automaton could achieve an identical response on every occasion, and an artist's individuality will inevitably impel him to contribute something different to each performance, however minor the variation; every audience too is unique in composition and reaction, and there is an interplay of influence across the footlights. Members of an audience should never underestimate the importance of their contribution to the success of a performance, for an appreciative reception gives a great psychological uplift to the players on the stage, which in turn tends to enhance the standard of accomplishment.

|

Characteristically, John does not quail before issues bordering upon controversy. Whenever practicable, he would like to see encores given when an audience unequivocally demands them and not limited exclusively to predetermined numbers as is usually the case. On the other hand, he recognises that encores need to be situated conveniently in terms of staging and dramatic action if the plot is not to be disrupted by misplaced or excessive encores; and, having been composed with encores in mind, certain numbers do lend themselves more readily to this treatment than others. Furthermore, extending the availability of encores would necessitate a measure of planning, as a successful encore is not simply an action replay' or replica of the original piece, but introduces some new element, as John Reed superbly illustrated in "Here's a How-De-Do!" and "Never Mind the Why and Wherefore".

About fans he expresses himself unhesitatingly: they are basically wonderful, and, whenever circumstances permit, he enjoys chatting with them before or after the show, with the result that relations frequently ripen into genuine friendship. He tries to be unfailingly courteous to his fans, and asks no more of them than that they return the compliment, allowing him reasonable privacy and freedom to divide his time evenly among them.

On the subject of critics, he chooses his words more carefully: if he believes the adulatory, he should also believe the censorious; it is self-deceptive if tempting to accept only favourable reviews, therefore critics as a whole should be equally read or equally ignored. On balance, he tends to the latter position, taking press comment with a pinch of salt, not because he feels himself above criticism, but because, having received diametrically opposed reactions to essentially similar performances, he has come to the conclusion that Criticism is largely a matter of opinion. The advice offered is not only varied, but frequently contradictory. John is convinced that a conscientious artist knows instinctively when he has given of his best, or nearly so, and when he has not, and as such remains his own constant and implacable critic.

Each year John Ayldon appeared in the Gilbert and Sullivan operas about three hundred and fifty times. and, you may be tolerably certain that the level of performance approached the optimum - a feat of consistency by any criteria. Perhaps the most fitting tribute one can pay to a member of a profession which cherishes its standards jealously is to say that, in the best sense of the word, he is a true professional.

| Artist Index | Main Index |